When the Democrats Became God

The idea that the government should alleviate all human suffering took hold in the late 19th century.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Nowadays, numerous Democrats take it for granted that if any individual or group — or at least those that are reliably leftist — faces a problem, it is the government’s responsibility to solve it. This is actually a very old idea that first gained traction among the Democrats in the late nineteenth century.

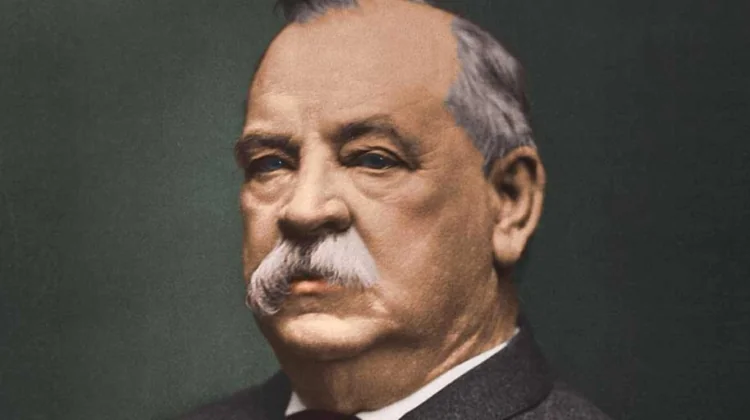

In his last annual message to Congress of his first term, delivered on December 3, 1888, after he had already lost his bid for reelection, President Grover Cleveland decried the growing gap between rich and poor in America: “We find the wealth and luxury of our cities mingled with poverty and wretchedness and unremunerative toil…. The gulf between employers and the employed is constantly widening, and classes are rapidly forming, one comprising the very rich and powerful, while in another are found the toiling poor.”

This was one of the earliest enunciations of the idea that it is the responsibility of the federal government to relieve the poverty of some American citizens. Cleveland’s call for social justice was the beginning of the Democratic Party’s downhill slide into large-scale state control, and of the ever-popular idea that the government must forever grow and become ever more intrusive into the citizenry’s daily lives in a messianic attempt to end human misery.

Cleveland added: “Any intermediary between the people and their Government or the least delegation of the care and protection the Government owes to the humblest citizen in the land makes the boast of free institutions a glittering delusion and the pretended boon of American citizenship a shameless imposition.”

Yet Cleveland’s non-consecutive second term began with the Panic of 1893, a severe depression that lasted for several years and destroyed his popularity, although it had been brought on by his predecessor Benjamin Harrison’s policies, rather than by his. Cleveland was certain that among the chief causes of the Panic was the Sherman Silver Act of 1890, which allowed for coinage of silver in addition to gold. Silver was more plentiful and worth less than gold, so the coinage of silver led to more money in circulation and, consequently, to inflation.

Western and Southern farmers were happy with that inflation, as it enabled them to pay their debts with money that was worth less than the money they had borrowed; however, businesses suffered, and the higher prices hurt individual Americans. Cleveland resisted calls for drastic government action and pressed for repeal of the Sherman Silver Act, placing the nation’s money supply on a firmer basis and combating the inflation.

Nonetheless, the depression lasted for the whole of his second term, and Cleveland came under immense pressure. In 1894, a labor activist named Jacob Coxey led a group of unemployed men, which came to be known as “Coxey’s Army,” in a march on Washington to demand government action: a massive public works program to help those without jobs. Coxey was widely dismissed as a crank and arrested. His “army” was dispersed, and nothing came of his demands until they became Democratic Party policy much later.

By the time that Coxey and his army marched on Washington, Cleveland seemed to have forgotten the “care and protection” that in 1888 he said the government owed to the “humblest citizen.” Though Coxey’s Army was quickly dispersed, the bitterness over the injustices of unrestrained monopolies remained. Massive corporations were indeed often unjust to workers. A political cartoon during the Pullman Strike depicted Pullman crushing a worker between two huge stones, one labeled “Low Wages,” and the other “High Rents.” If employers would not deal justly with their employees, increasing numbers of Americans believed that it would benefit all Americans if they were legally compelled to do so.

Opponents of this idea countered that expanding federal power to check that of monopolies would simply substitute one massively powerful authority that could work its will unopposed for another. Throughout the twentieth century, evidence multiplied showing that these critics were correct. Yet in the twenty-first, monopolies emerged that were characterized by a disquieting willingness to restrict Americans’ constitutional freedoms, particularly the freedom of speech; only the federal government had the ability to stop them, although little was done, and many who opposed the uncontrolled growth of federal power also opposed actions against these monopolies for that very reason. The proper balance had to be found. Over a century and a quarter later, it has still not been found.