Book and Dagger: How Scholars and Librarians Became the Unlikely Spies of World War II

Espionage and the importance of humanities scholars.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

[Want even more content from FPM? Sign up for FPM+ to unlock exclusive series, virtual town-halls with our authors, and more—now for just $3.99/month. Click here to sign up.]

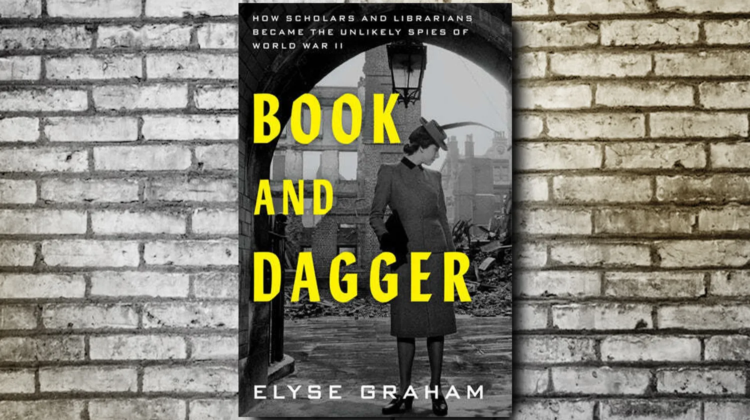

Ecco, a subdivision of Harper Collins, released Book and Dagger: How Scholars and Librarians Became the Unlikely Spies of World War II by Elyse Graham on September 24, 2024. The book has 376 pages, inclusive of footnotes, endnotes, and an index. It is not illustrated. Graham received her PhD from Yale; she currently teaches English at Stony Brook.

The Washington Post raved about Book and Dagger. “Graham’s account is well-researched and scrupulously footnoted, but she also writes with a pulpy panache that turns the book into a well-paced thriller.” The Wall Street Journal praised “an almost breathless sense of wartime romance and drama. It makes for entertaining, atmospheric reading.” Publisher’s Weekly enjoyed “Graham’s exuberant prose … a colorful salute to some of WWII’s more bookish heroes.”

I liked this book, but did not love it. I would, though, recommend it to anyone intrigued by the title. More on my reaction to the book, below, after a somewhat choppy summary of a somewhat choppy book.

In the summer of 1941, President Roosevelt told his former Columbia classmate and World War I military hero William J. Donovan that “We have no intelligence service.” Other nations had established spy agencies with centuries of continuous experience. In 1929, Secretary of State Henry Stimson had closed the Cable and Telegraph Section, a spy service created during World War I, declaring, “Gentlemen do not read each other’s mail.” In 1941, World War II loomed. America needed nationally coordinated intelligence gathering. Donovan left his law practice to become the first director of a new agency, the Office of Strategic Services or OSS. It would eventually become the CIA. A statue of Donovan stands in the lobby of the CIA headquarters building in Langley, Virginia.

Joseph Curtiss, a Yale English professor, came from a background so comfortable that he did not draw a salary. He didn’t even have a social security number. Curtiss’ superior visited him, told him to go to the Yale club in New York City, and wear a blue suit and a purple tie. A man there would light, then extinguish, a cigarette. The man Curtiss met was in the new OSS. He recruited Curtiss to spy for America. Curtiss would serve under cover as a Yale professor. They needed a real professor to make the cover work.

“Hundreds of others like him” – that is, scholars and librarians – were similarly recruited. Donovan’s innovation in creating the OSS was to seek out scholars. Donovan was an Ivy-League-trained lawyer. He was used to “reading the literature,” so he knew to value scholars and scholarship. “The war may have been fought in battlefields, but it was won in libraries,” Graham insists.

Adele Kibre was a PhD medievalist who made her living by photographing documents in Europe for US scholars. She returned to the US as the Nazis rose to power. The OSS recruited her to return to Europe as a spy and exercise her skill at photographing documents. Carleton Coon, a Harvard anthropologist and scientific racist, hoped that being recruited to the OSS would allow him to fulfill his goal of emulating Lawrence of Arabia. Sherman Kent was a Yale history professor and curator of Yale library’s war collection. In the OSS, he organized the information arriving at the agency. He could “throw a knife better than a Sicilian.” He could also use a carefully folded newspaper as a weapon.

New recruits were sent to training camps. One was in the Catoctin Mountains in Maryland. Training lasted for three weeks. Trainees had to prove that they could be trusted with secrets while under tremendous pressure. One trainee, recruited from Europe, had already survived Gestapo interrogation. Undergoing a simulated interrogation at the Catoctin camp, he experienced such severe PTSD that he had to be released.

A British Royal Marine named William Ewart Fairbairn taught trainees how to fight dirty, and how to kill coolly. “Gentlemanly combatants end up dead … dispose of your opponent as quickly as possible.”

Curtiss and his peers were being trained with live ammunition. Knives were preferred, though, for their silence. An opponent’s coat and trousers could be turned against him; pull them halfway down; this handicaps his movements. Trainees also did classroom work, including memorizing the ranks of the Nazi and fascist Italian armed forces. They were also taught the little details of spy survival, for example, keeping highly flammable cellphone between sheets of important papers to facilitate burning those papers when the moment came to do that. If captured and tortured, the captive’s goal would be to endure for forty-eight hours, so that comrades on the outside could escape the round-up net.

Some Americans were trained in the UK. Mystery writer Selwyn Jepson trained Adele Kibre. Jepson said that “women were very much better than men for the work” because they have a “far greater capacity for cool and lonely courage than men.” A favored trick of female agents seeking information was to publicly state a falsehood. Men listening would rush to correct the confused woman, thus providing her with the information she sought. (Nowadays, on the internet, this tactic is known as Cunningham’s Law.)

Beaulieu Palace House and surrounding structures, located in New Forest southwest of London, provided a training spot for the Special Operations Executive, or SOE. The forest shielded trainees from German reconnaissance planes. Trainees came from over a dozen countries; training lasted three weeks. Students were taught survivalist skills, in case they were on the run and needed to snare a rabbit or catch a fish for food. Students were also encouraged to read spy novels.

Johnny Ramesky, born Jonas Ramanauskas, a Scottish safe cracker and son of Lithuania immigrant parents, taught trainees his trade. In spite of his wartime service, Ramesky never escaped the lure of criminal behavior. He would eventually die a prisoner in 1972.

Radio operators, aka “wireless telegraphy” operators, had the shortest lifespan once behind enemy lines. They were expected to be captured within six months. Beaulieu trained wireless telegraphy operator Noor Inayat Khan. Khan was executed in Dachau, along with her fellow agents Yolande Beekman, Madeleine Damerment and Eliane Plewman. SOE agent Vera Leigh and four other women, Graham writes, were injected with a paralyzing drug before being tossed alive into an oven. “One staffer estimated that half of the women who infiltrated France for the SOE died in action and their deaths were often so cruel and degraded that no novelist would use the stories.” Agents were issued cyanide capsules called “L-pills” or “lethal pills.”

Graham emphasis the importance of library work by mentioning that the British Patent Office had a patent for the Enigma machine since 1927, including a “full technical dossier in English, with accompanying diagrams.” Graham implies that had a skilled librarian performed a thorough search, this patent would have been found and used to the Allies’ benefit.

Joseph Curtiss was sent to Istanbul, a spy capital in neutral Turkey. As part of his cover, he shopped for and bought multitudes of books. His real job was to find Axis spies and recruit them for the Allies. “For the period of his novitiate” a double agent “is not an asset, but a liability,” according to one spymaster. The double agent must be given real information he can convey to his superiors before he can be believable at providing false information. Curtiss’ other task was orchestrating whisper campaigns. Graham lists ways that spies in Istanbul conducted whisper campaigns to spread propaganda. These methods included speaking loudly in public, on phone lines known to be tapped, and leaving notes in public trash. Curtiss was eventually ordered to assassinate someone. Whether or not he did so is not recorded.

Adele Kibre worked in neutral Sweden. Graham’s book is mostly lighthearted, but she devotes a paragraph to detailing how “neutral” Sweden avoided the fate of its neighbor to the south, Nazi-occupied Poland. In Wisniewo, Poland, “German soldiers forced civilians to lie in the mud and rolled over them with tanks” In Bydgoszcz, Nazis “repeatedly laid out the corpses of civilians, many times, in the shape of a swastika.”

The Sweden Graham describes sounds not quite neutral. For example, Sweden banned Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator, because the film criticized Hitler. “Firsthand accounts of Nazi brutalities in Norway” were banned in newspapers. “Sweden even allowed Germany to use Swedish trains and railway tracks to carry troops and military equipment to Norway.” Graham quotes Joachim Joesten, a German journalist and observer of Swedish life in 1943. “The persecution of Jews in Nazi-held countries was soft-pedaled, the horrors of the concentration camps were wholly dropped out, blitzkrieg, invasions, and all the endless atrocities committed by the Nazi hordes were reported and commented on only in the meekest undertones … even the tamest bit of criticism directed against the Nazis had to be invariably compensated by a corresponding poke at the Allies.”

American spy Adele Kibre, armed with a Contax microfilm camera, arrived in Sweden in 1942. What did her handlers want her to photograph? “They really want everything.” “I don’t care how you go about acquiring this material,” she was told.

Kibre acquired much material through straightforward means. She bought openly marketed books and periodicals. Some material, like difficult-to-acquire Nazi publications, required spy skills. Graham occasionally departs from the reporting of known facts. She presents scenes she imagines based on known facts. When Graham does this, she alerts the reader that the following scene is her fictionalized account based on known facts. In one such imagined scene, Graham posits a way Kibre might have acquired materials she wanted from Nazis in Sweden. Kibre attends a party of local Germans. Kibre’s parents and her sister were involved in Hollywood’s film industry. Kibre lets this be known. A German approaches her. Kibre says that Jews sabotaged her Hollywood career. The German believes Kibre is sympathetic to Nazism. Kibre gains access to the Nazi publications she wants.

Back in the States, Sherman Kent planned for an invasion of North Africa. Kent had to convince military men that pure research skills were necessary for a successful invasion. Graham dramatizes a scene of Kent doing so by pointing out to military leaders that he knows in advance of an invasion, and that he know where and when that invasion will take place. He has learned this by exercising his scholarly skills. He tells his military counterpart that library research is necessary for this invasion. His research will provide necessary information on railroads, ports, tides, etc. Kent’s library research was so fully informative and helpful that the military assigned him and his team many more tasks.

Graham devotes a chapter to the Allied sabotage of Norway’s Vemork hydroelectric plant. The plant produced heavy water, a resource that might have potentially been used by the Nazis to make atomic bombs. Along the way she sketches out how nuclear weapons work. Graham salutes Lise Meitner, an Austrian Jewish physicist. Meitner made important discoveries leading up to the military use of atoms, but her partner, Otto Hahn, took all the credit and the Nobel Prize was given to him alone, excluding Meitner.

Varian Fry was a Columbia University graduate student. He was the privileged son of a Wall Street executive, a Presbyterian, and a Harvard grad. According to his son, he was also a “closeted homosexual.” As part of the quickly assembled Emergency Rescue Committee, Fry delivered visas to refugees trapped in France who were “writers, musicians, and other cultural luminaries.” Through social connections, the Emergency Rescue Committee was able to obtain these visas with the help of first lady Eleanor Roosevelt. To aid his work, Fry used both legal means and means rendered illegal by the occupation. He was in Europe for thirteen months before he was forced to leave. Graham estimates that Fry helped approximately fifteen hundred refugees escape Europe. The Tablet credits Fry with 2,000 rescues, among them “Hannah Arendt, Marcel Duchamp, Marc Chagall, Max Ernst, Claude Lévi-Strauss, and André Breton.” Fry is one of only five “Righteous” Americans recognized by Yad Vashem.

Graham summarizes Operation Mincemeat, an intelligence operation designed to fool Germany about the 1943 Allied invasion of Sicily. The corpse of a homeless man was disguised as a British officer and planted on the coast of Spain. The corpse was attached to documents suggesting that the Allied attack would take place on Greece, not Sicily. Graham also summarizes D-Day. She mentions the “ghost war” tactics of, for example, creating fake military installations that fooled German reconnaissance planes. Before D-Day, the Allies engaged in many subterfuges to trick Germans into believing that they would not attack on Normandy. For example, Patton toured Egypt and met with the general of the Polish corps stationed there. This was done to distract from Normandy plans. M.E. Clifton James, an Australian actor who looked like Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, was dispatched to Gibraltar and Algiers, again, to distract attention from Normandy. And American engineers queried Swedish rail employees how much weight their trains could bear, in order to imply that the Allies might attack through Norway. Wall Street and British High Street traders adjusted their behavior for the same reason – to distract from Normandy and to, in this case, suggest that an attack on Norway was imminent. Graham reports that thanks to the ghost war, “a staggering ninety divisions of German troops that could have joined the fight in Normandy remained elsewhere.”

Graham devotes her penultimate chapter to a discussion of the scholars assigned to finding, assessing, and protecting artworks looted by the Nazis. She describes the team members’ bona fides, their affiliation with American institutions, and then reports on the massive art looting carried out by the Nazis. American scholars had to rely on luck and informants to find art. Those who facilitated the arts’ looting were surprised when they were arrested and imprisoned. American scholar soldiers had to rescue art from a booby-trapped Austrian salt mine. In the final days of the war, faithful to the scorched earth spirit of Hitler’s “Nero decree” intentions, Americans had to rescue art not from looting Nazis, but destroying Nazis. American governmental officials wanted rescued art to be shipped to America, for “safekeeping.” The scholars of the art rescue teams objected and this never occurred. Russians, on the other hand, did take art back to the Soviet Union.

Graham, in her final chapter, reasserts her thesis. The bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki “may have ended the war, but the research and analysis performed by the people described in this book won it.”

Sherman Kent went on to edit a CIA publication. In that capacity, he wanted to publish an article that would prove the value of the kind of intelligence work scholars could and did perform. In 1951, Kent recruited a team of scholars, using only the Yale Sterling Memorial Library’s resources, to lay out, in detail, the US order of battle, or “total military configuration, from the leaders to the troop units to the equipment.” His team of scholars were able to do that, with 90% accuracy, and even more, creating an “encyclopedia” of “the types, placement, and strength, of all the US military’s combat ships and planes.”

Once that was accomplished, Kent went further. He asked a Sovietologist to reformat the report as if it had been created by Soviets. Kent gave the report to his CIA boss, who gave it to Truman, and, as Kent said, “the —- hit the fan.”

Again, I enjoyed this book, and I’m glad I read it. I would recommend it to anyone interested in espionage, World War II, and the role of scholars in wartime. Graham often displays an enthusiastic writing style. Her imagined scenes – always identified as such – read like fun pulp fiction. I did have problems with the book. I’ll discuss them, below, from the minor to the major.

This book really should have been illustrated. Graham introduces many intriguing characters who appear only for a few pages. Graham’s information about these characters is limited and we don’t really get to know, for example, Joseph Curtiss or Adele Kibre. I would stop reading and turn to the internet to try to find photos of these characters so I could get to know them better. In many cases I could not find good photos. I did find good photos, and even film footage, of Fairbairn, and those images fleshed him out beautifully. I would like to see a photo of a newspaper folded into a knife, or the salt mine full of looted artworks.

Most readers with any interest in World War II will be familiar with a fair amount of the material in this book. D-Day, the role of art scholars, the raid on the heavy water plant, have all been the subject of major movies: The Longest Day, Saving Private Ryan, The Monuments Men, and Heroes of Telemark. Operation Mincemeat is the subject and name of a successful Broadway musical. Graham’s sources tend to be popular histories of the events she covers. For example, for her chapter on the sabotage of the Vemork hydroelectric power plant, Graham repeatedly cites Knut Anders Haukelid’s book Skis Against the Atom: The Exciting, First Hand Account of Heroism and Daring Sabotage During the Nazi Occupation of Norway. Why read Graham’s summary of Haukelid’s work, when you can read the original? The other option would have been for Graham to do what she praises her subjects for doing – deep, scholarly, original research. Go to the archives; interview descendants of the key players, and come up with some new information that has not been published already.

My biggest problem with this book was its episodic nature. Book and Dagger does not present a straight-line narrative from the first page to the last. Rather, it presents disconnected anecdotes. These anecdotes are often told “Paul Harvey” style. In his “rest of the story” broadcasts, Harvey would often withhold the key who, what, when, where, why, how information until revealing it in the final sentence. Graham, perhaps to build suspense, often does something similar. For example, on page 252, she first mentions an artist who marketed his forged Vermeers to the Nazis. She doesn’t name this forger, Han van Meegeren until page 267. Given how many unconnected characters and anecdotes the book introduces, most who appear only for a few pages, I wish that the W, W, W, W, W, H of each character were introduced in a more orderly manner.

Reading the early chapters, I assumed that the characters introduced there, namely Joseph Curtiss, Adele Kibre, Sherman Kent, and Carleton Coon, would become the main characters of the rest of the narrative. I assumed that the book would deliver on the promise of its subtitle and of statements like “The war may have been fought in battlefields, but it was won in libraries.” I thought that the book would deliver on this promise by exploring the careers of Curtiss, Kibre, Coon, and Sherman in depth and in detail. I hoped to get to know them and understand how a scholar uses scholarly skills to function under intense pressure and win a war. Graham does a bit of this but it reads as a dry summary rather than a lived experience. Graham reports that Curtiss was ordered to assassinate someone; she could find no record as to whether he did or did not.

Given how well-written Graham’s few, brief imaginary scenes were, I wish, rather than writing this book, or, perhaps, in addition to this book, she had written a novel based on Curtiss, Kibre, Coon, and Kent.

When I found myself reading about D-Day, Operation Mincemeat, and the raid on the heavy water plant in Norway, events I’d seen treated in other media, I became annoyed. I felt that Graham had strayed from the purview clearly outlined in her book’s title. The work of art scholars in finding and protecting looted artworks even felt like a tangent, given that that work took place as the war was winding down, and Graham promised that she would prove to me that scholars won the war, not that they helped in mopping up as the war was ending.

Again, Graham is a good writer. Her introduction to Joseph Curtiss, the nonsalaried Yale English professor who was mysteriously summoned to New York City’s Yale club, where, wearing a blue suit and a purple tie, he was to meet with a handler who would light, and then extinguish a cigarette, delighted and intrigued me. I wanted to read an entire book allowing me to get to know Curtiss better, and to learn how his scholarly skills won the war my father fought in in the sweaty jungles of the Pacific Theater. I want to know how Adele Kibre felt when she was taught how to knife someone to death while walking casually down the street. I want to know more about Sherman Kent than the book’s repeated and cliched descriptions of him.

I don’t know if more data about these characters exists in government archives and family, student, and coworker folklore and Graham simply did not dig deep enough to find this material, or if there is no such data available. In either case, again, given that her imagined scenes are so fun to read, I wish Graham, rather than writing a non-fiction book, had written a novel with characters based on Curtiss, Kibre, and Kent. Carleton Coon the racist would clearly be her bad guy.

After introducing Curtiss, Graham immediately goes off on a tangent about Nazi book burning. This disappointed me. It had little to do with the main thrust of her book, and Nazi book burning is well known. Given the lack of a straight line narrative and the book’s episodic structure, information is repeated. Nazi looting and destruction of books is discussed twice. “Pocket litter,” or the bits of paper in the pocket, used to support a spy’s cover story, is discussed repeatedly. Readers are twice told that Sherman Kent could “throw a knife better than a Sicilian” and that he swore like a sailor, and twice told how to work a book cipher, and twice told that while other nations had centuries of spycraft behind them, America entered WW II with almost no intelligence gathering agencies.

Graham, herself a humanities scholar from an Ivy League institution, often repeats the larger lesson of her book, that the humanities matter, and that even so physical an activity as warfare requires scholarly skills for success. These are good messages, but, again, an in-depth treatment of the wartime activities of scholar spies would have made the point better than Graham simply stating it over and over.

Amazon reviewer Jean Cowan points out a more serious flaw in Graham’s book. On page 72, Graham reports that in 1933, the SOE attempted to undermine Himmler using fake postage stamps. The SOE was founded in 1940. The fake Himmler postage stamps date from 1943 or 44. On page 36, Graham locates Beaulieu “about a hundred miles southeast of London.” Beaulieu is southwest of London. Graham uses Varian Fry’s book Assignment Rescue as her source for her claim that Fry rescued 1,500 refugees. Yad Vashem and other sources say that Fry rescued 2,000 refugees. Assignment Rescue is the abridged, Scholastic books version of Fry’s Surrender on Demand. It is meant for high school students. Perhaps Yad Vashem would have been a better source for the number of persons Fry helped to rescue. Graham refers to Noor Inayat Khan, a resistance radio operator who was murdered in Dachau, only as “Nora Inayat Khan.” “Noor” is a common name for Muslims; it means “light.” Of course Khan sometimes went by “Nora,” but most sources provide both her birth name and her adopted English name. I think it would have been more gracious of Graham to provide both Khan’s birth and adopted names. Also, though Khan is mentioned in the book, she is not listed in the index.

Danusha V. Goska is the author of God through Binoculars: A Hitchhiker at a Monastery.