How Harding Got the Twenties Roaring

Tariffs and tax cuts revitalized the economy.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

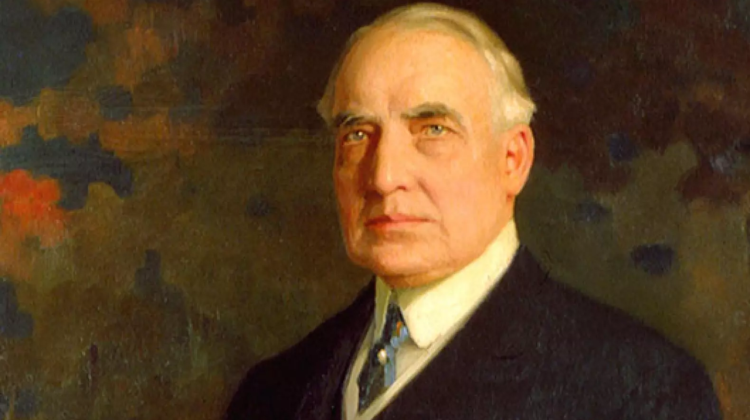

The 29th U.S. president, Warren G. Harding (1921-3) gets scant respect; his presidency is generally ranked as a failure. About the only things that Americans today remember about him, if they remember anything at all, are that he had a mistress, his presidency was engulfed in scandal, and he was out of his depth as president, winning the election only because he was handsome and women had just been given the right to vote. This is, however, a caricature. Harding was actually a competent president who got the American economy on its feet after eight years of Woodrow Wilson’s leftist misrule.

There is no doubt that Harding was no straitlaced Puritan, and he does appear to have had more than one extramarital affair. Insofar as the president should be a moral exemplar for the nation, he did fail, but that is not a constitutional duty, and his affairs did not become known until after his death.

Regarding the Teapot Dome Scandal, Harding’s responsibility for it lies only in the fact that he appointed and trusted the official who was primarily involved, Interior Secretary Albert Fall, in the first place. One may fault Harding for being such a poor judge of men as to have thought Fall would be honest and upright, but that is the sort of misjudgment that can befall anyone, and there is no guarding against it.

The idea that Harding was not capable of being a competent president stems largely from his own statements. Harding himself abetted the impression that he was overmatched in the presidency with several self-deprecating expressions of frustration, including: “I am not fit for this office, and should never have been here.” And at one point, he told a friend: “I can’t make a damn thing out of this tax problem. I listen to one side, and they seem right, and then—God!—I talk to the other side, and they seem just as right.”

But the fact that Harding was not a great thinker or inspiring speaker does not mean that he was an ineffective president. Nor does the fact that he was a humble man who was keenly aware of his limitations.

Above all, what Harding did for the economy ensured that as the nation emerged from the First World War, it would enjoy an economic boom. Eight years of Wilson had sapped the nation’s energy and burdened it with taxes and regulations. Harding got the economy going again—indeed, booming, with policies that ushered in the Roaring Twenties, a time of prosperity and national exuberance after the grim and pious internationalism of the Wilson years.

The country was much better off with the simple and humble Harding in the White House than it was when the renowned intellectual and crusader for civilization Wilson was there. As president, Harding moved decisively to end a postwar recession. He called a special joint session of both houses of Congress on April 12, 1921, and told the assembled representatives: “I know of no more pressing problem at home than to restrict our national expenditures within the limits of our national income”—that line drew applause, a sign that these were times very different from our own—“and at the same time measurably lift the burdens of war taxation from the shoulders of the American people.” He got income taxes cut by about 40 percent and tariffs raised, and the American economy responded quickly: the twenties began roaring.

In his address to Congress on April 12, 1921, Harding denounced “the unrestrained tendency to heedless expenditure and the attending growth of public indebtedness.” On June 10, 1921, Harding signed the Budget and Accounting Act, which was designed to provide oversight that would make federal spending more efficient and prevent it from spiraling out of control (yes, it was a precursor of DOGE). The Harding administration slashed $2 billion from the national debt and cut federal spending nearly in half.

Harding’s mix of higher tariffs, lower taxes, and restraints on spending led to a boom for American business, and thus also for the American workers those businesses employed. Unemployment dropped from 12 percent in 1921 to 2.4 percent on August 2, 1923, the day that Harding died in San Francisco while on a speaking tour.

Harding’s presidency deserves an honest reassessment, but that is unlikely to happen given the fact that most historians today share Wilson’s messianic globalism and visions of massive state control.