The First President Who Hated the Constitution

Here is where many of our troubles began.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Nowadays, contempt for the Constitution among those who have vowed to protect and defend it is so commonplace as to be hardly worth noting. Leftists pay lip-service to the venerable document, especially when they think they can use it to get in a plausible dig against the focus of evil in the modern world, Donald J. Trump, but mostly they just ignore it and pretend it isn’t there. Efforts to square their agenda with its principles end up with legal monstrosities such as Roe v. Wade. Yet while patriots are generally aware of this, few realize that the left’s contempt for the Constitution didn’t start with Barack Obama, or even Lyndon Johnson or FDR. It’s older than all of them.

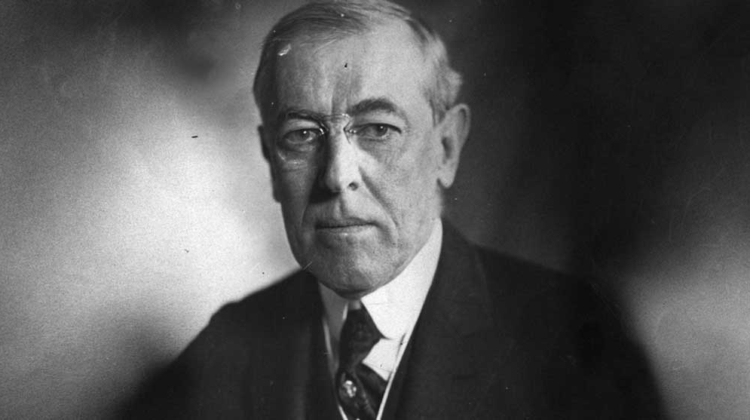

The American left’s contempt for the U.S. Constitution began with Woodrow Wilson, who was president from 1913 to 1921 and would have secured the title of worst president in history were it not for all the even worse Democrat presidents who have followed after him. For most of his career, Wilson was a professor, with an academic’s certainty and a smug assurance about how the nation should be run. Then, three years after he entered politics, he was president of the United States, determined to make the world over the way he was certain it should be ordered. The nation, and the world, has not yet recovered.

Early in his academic career, Wilson displayed impatience with the American system of checks and balances. What America needed, he opined, was an authoritarian strongman. In his 1885 book Congressional Government: A Study in American Politics, he lamented that “Congress must act through the President and his Cabinet; the President and his Cabinet must wait upon the will of Congress. There is no one supreme, ultimate head – whether magistrate or representative body – which can decide at once and with conclusive authority what shall be done at those times when some decision there must be, and that immediately.” This defect, he wrote, “in times of sudden exigency…might prove fatal.”

He was also an early advocate of the welfare state, calling for charitable obligations to be “made the imperative legal duty of the whole.”

All this would have remained within the realm of academic progressive theory had not Wilson decided to enter politics after serving as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910. He was elected Governor of New Jersey, serving for two years and gaining a reputation as a reliable progressive. In a crowded Democratic field with three-time loser and party leader William Jennings Bryan’s shadow looming over all the candidates, he attracted attention as someone who could be counted upon to further the progressive agenda but was also palatable to the “Safe and Sane” faction that was wary of Bryan’s taste for big government. At a deadlocked Democratic National Convention in 1912, Wilson was nominated on the 46th ballot.

Meanwhile, former President Theodore Roosevelt was enraged at his chosen successor, William Howard Taft, for not being “progressive” enough. The anger of Roosevelt and the “progressive” Republicans at Taft was the best thing that happened to the Democrats since Grover Cleveland was reelected twenty years before. Denied the Republican nomination, Roosevelt and his supporters bolted the Republican Party and created the Progressive Party, splitting the Republican vote and virtually ensuring the election of Wilson. Combined, the votes that Roosevelt and Taft received would have won them enough states to have resulted in a comfortable victory for the Republicans. But their votes weren’t combined, and Wilson was the one who went to the White House.

The Progressives called for restrictions on campaign contributions, lower tariffs, a social insurance system akin to Social Security, and other expansions of government regulation and power. Bryan, now the Democratic Party’s kingmaker, charged Roosevelt and the Progressives with stealing ideas from the Democratic program. Roosevelt responded cheerfully: “So I have. That is quite true. I have taken every one of them except those suited for the inmates of lunatic asylums.” And maybe some of those as well.

Never before had the U.S. elected a president who had expressed contempt for how the American government worked. Wilson and later Democrat presidents would proceed to ignore the aspects of those workings that they disliked, and to treat the detested Constitution as if it had no relevance to the current situation. The next Democrat to be elected president will no doubt act the same way.