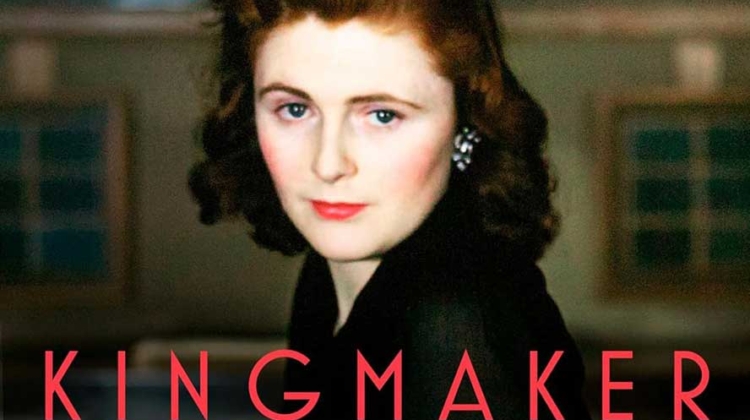

Kingmaker: Pamela Harriman’s Astonishing Life of Power, Seduction, and Intrigue

Sonia Purnell has written the definitive biography of an unforgettable woman.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

[Want even more content from FPM? Sign up for FPM+ to unlock exclusive series, virtual town-halls with our authors, and more—now for just $3.99/month. Click here to sign up.]

The other day a friend confided in me. She finished reading a book, went to Goodreads to review it, and realized that she’d read and reviewed it before. “Alzheimer’s?” she worried.

“No,” I replied. “Boring book.”

I’ve just finished reading a book I don’t think I’ll ever forget, about a woman I’ll be thinking about for a long, long time. Kingmaker: Pamela Harriman’s Astonishing Life of Power, Seduction, and Intrigue by Sonia Purnell was released by Viking on September 17, 2024. The book has 528 pages, inclusive of black-and-white photographs, endnotes, bibliography, and index. Purnell is a British journalist and the author of previous biographies of former British prime minister Boris Johnson; Clementine Churchill, the wife of Winston Churchill; and American World War II spy Virginia Hall.

The New Yorker calls Kingmaker “riveting and revelatory;” the New York Times “rollicking,” The Financial Times, “insightful, fascinating, flawless, vivid;” and People a “must read.” Over four hundred Amazon readers award the book an average of 4.5 stars.

Given potential confusion, this review will refer to Pamela Digby Churchill Hayward Harriman as Pamela, rather than by any of her four surnames. Pamela was born to British nobility in 1920. She worked intimately with Winston Churchill during WW II to defeat the Axis powers. President Bill Clinton appointed her as the U.S. ambassador to France. Ambassador Harriman died in Paris in 1997, at age 76 while swimming twenty lengths in a pool.

Pamela had countless wealthy, prominent, and powerful lovers, and she was a socialite who rubbed elbows with an astonishing roster. Pamela met news makers from Adolf Hitler to Nelson Mandela, from Ernest Hemingway to to T.S. Eliot to Truman Capote, from Douglas Fairbanks Jr. to Jane Fonda, from Edward R. Murrow to Christiane Amanpour, from Ronald and Nancy Reagan to Bill and Hillary Clinton, and of course almost all of the Kennedys. Margaret Thatcher, an admirer, praised her services to her homeland. Senator Strom Thurmond denounced her as the “Whore of Babylon,” but Senator Bob Dole was a “longtime admirer.” Her career as a courtesan was enough to render her biography-worthy, and there have been previous tell-alls, films, and plays that depict her.

Purnell’s new bio stands out. Purnell argues, with full support from archival documentation and contemporary interviews, that Pamela used her skills at feminine seduction not just to make money, but also to make history. Pamela’s trajectory is all the more remarkable given that she was dismissed in her youth. Other kids bullied her. At debutante coming-out events, high-born British girls sought equally high-born husbands. Young bachelors, who might have been Pamela’s suitors, and fellow female debutantes as well, would publicly and audibly mock Pamela as a fat, stupid, silly, dowdy, and equine country girl. “Men seem to have taken pleasure in her humiliation.” Nor did Pamela have any real education to speak of, and her parents practiced an aristocratic hands-off approach to parenting. In her early life, no one was behind Pamela, believing in her, encouraging her, and pushing her forward. Pamela was a self-made woman. And what a woman she made of herself.

Purnell has done her homework. Kingmaker has been thoroughly researched, and that research covers every aspect of Pamela Harriman’s life, from the lack of bathrooms in her childhood mansion to the sex acts she learned from Prince Aly Khan, from the color of carpets in her many homes to the gifts she sent those she manipulated to achieve her ends.

Purnell’s style is journalistic. She focuses on presenting supported facts in a crisp, “And then, and then, and then” narrative. Purnell does not resort to purple prose, even though there is lots of juicy material. In spite of all the sex, this is not a bodice-ripper. Episodic, ironically dry accounts of “And then Pamela took this lover and then Pamela took this lover … ” began to feel tedious. It was only when the book turned its focus to Pamela’s political ascendancy in the U.S. that the book became a page-turner for me.

I’m a big fan of Gone with the Wind, though I do condemn its racism. I’d previously thought of Scarlett O’Hara as the epitome of a heroine who uses feminine wiles to advance herself and her loved ones through war and catastrophe, from wretched poverty to lavish security.

“Truth is stranger than fiction,” they say. The fictional Scarlett must take a back seat to the factual Pamela. I devoted to Kingmaker the kind of focus I devote when reading demanding scientific material. Though I am her fellow woman and no science nerd, I think I understand mRNA vaccines better than I understand Pamela.

On page after page, I stared, asking, “How the heck did she do that?” How did she hop from lover to lover when it has taken me years to get over one guy and accept new affection into my life? How did she retain contacts, even after men behaved abusively toward her, contacts she could later exploit to her own advantage? How did she survive the scorn society heaps on promiscuous women? How did she manage to find lovers who would bankroll her extravagant lifestyle, sometimes years after their affairs ended, and she had already moved on to other men? How did she manage the time and energy to live so many different lives – wife and mother in England, courtesan to two of the wealthiest men on the continent in France, show business spouse and then, after most retire or die, world-changing political operative and diplomat? How did she handle the jet lag? Skiing in Switzerland, visiting her son in England, spatting with step children in New York, hosting multi-million-dollar fundraisers in DC? When she was in her seventies, she slept five hours a night. It takes me at least an hour to recuperate from grocery shopping and focus on a new task. Pamela’s ability to turn on a dime took my breath away.

I think this is probably the best, most detailed, most researched book that will ever be written about Pamela, and yet I still do not understand her. I never felt while reading this – as I have felt while reading Gone with the Wind – that I understood how someone so different from me could do things that for me would be unthinkable. That’s no criticism of the book. I wondered, while reading it, if Pamela lacked an interior life. Maybe she was all drive, all action, no reflection. I don’t know.

Pamela has been condemned for her promiscuity. Purnell does not condemn her. Purnell does, though, depict Pamela as a poor mother who caused her son, Winston Spencer Churchill – named after his grandfather – to be emotionally wounded for life. Pamela frequently left her weeping and lonely son with nannies, friends, relatives, her current lover, and, ultimately, at Eton, a boarding school he hated. Late in life, drowning in wealth, she was financially generous to him, his wife, and her grandchildren, but his criticisms of her show that money and private jets could not heal his childhood wounds.

Pamela was born to a noble family with “four hundred years of wealth and entitlement.” She was a girl, though, so she merited no education, no large inheritance, and no expectations. The family home had fifty rooms but “no bathrooms.” Purnell does not explain how bodily functions and hygiene were managed; I wish she had. “Everybody in the village worked for daddy.” Until she was fourteen, when at home, Pamela was relegated to a nursery staffed by a nanny. “She rarely saw a boy, never mind spoke to one.”

There was no chance that Pamela would ever have a career; she had to snag an upper class husband. Pamela failed at this, and, desperate, she married a man she barely knew. Randolph Churchill was the firstborn son of Winston Churchill, who, in 1939, was not yet prime minister. Randolph was about to go to war, and he felt it necessary to produce an heir. He proposed to nine women, all of whom turned him down, probably because he was a widely hated, obnoxious drunk. Pamela was as desperate as was Randolph, and they wed. Randolph did not pretend to love Pamela. He called his marriage “Hitler’s fault.” Randolph demanded Pamela’s awe, and also her womb, from whence he demanded an heir. This would not be easy, as his drinking interfered with his performance. Also, he was open about his extramarital affairs. Otherwise, “intimacy was anathema to him,” perhaps because, when he was a child, he was molested at boarding school by an adult man. Pamela blamed herself; she was “fat and frumpy.” Randolph’s spendthrift ways prompted him to use Pamela’s dowry to pay his debts. Dutifully, she rubbed her husband’s feet.

Randolph’s father, Winston, became prime minister in 1940, and, of course, he also became a larger-than-life figure in the battle against, and eventual defeat of the Axis powers. Winston and Clementine Churchill, unlike their son Randolph, were entranced by Pamela. Pamela gifted Winston with a pen; he used that pen to sign his wartime papers. She would sit on Winston’s bed and make him laugh. Pamela “adored” Winston, believing in him “more than any god.” When Winston became prime minister, Pamela moved into Downing Street. During the Blitz, she and Winston shared a bedroom. Heavily pregnant, on the bottom bunk, she said “I have one Churchill on top of me and one inside me.”

Winston began using Pamela at official events. Suddenly her “red hair, bright blue eyes, and translucent skin” were recognized as Britain’s secret weapon. He inducted her into his tiny inner circle, dubbed the “padlock.” She was assigned to placate Charles de Gaulle after the Brits fired on the French at Oran. Cecil Beaton photos of baby Winston and his attractive mother appeared in LIFE magazine, in an attempt to seduce Americans into supporting the British in World War II. In 1941, American President Franklin Roosevelt dispatched envoy Harry Hopkins to London. Winston deployed Pamela’s “cocktail” of “flattering attention, smoldering sex appeal, and impressive grasp of geopolitics.” Pamela quickly became “the apple of Harry Hopkins’ eye.”

Randolph made further demands on Pamela. She had to settle his debts. With no idea how to do so, Pamela went to Max Beaverbrook, publisher of the largest circulation newspaper in the world. He “invested in tight-fitting evening frocks, high heels, and natty tailored suits to help her in her new role.” Averell Harriman, a “dark haired Lothario of vast wealth,” arrived to administer Lend-Lease. Back in DC, Harry Hopkins had told Harriman that he must meet Pamela. Pamela, meeting the 49-year-old, “knew what to do and was willing to do it – above all, for Winston and her country … As the bombs whined and crashed, Averell was peeling off that gorgeous golden dress … Pamela lay naked in the arms of a man who might bring the horror to an end … Her true war work had begun … Her pillow talk was … influencing high-level policy on both sides of the Atlantic.”

Winston and Clementine heartily approved of their daughter-in-law’s extramarital war work. They sided with Pamela over their reprobate son. Averell, one of the richest men in the U.S., began to provide Pamela with an allowance, a car, a petrol ration card, and other cadeaux. Beaverbrook, grateful for her help to Britain’s war effort, also paid her. Winston and Clementine Churchill also began paying Pamela an allowance. So grateful they were to her for her wartime service that they paid that sum for the rest of their lives.

Pamela did not “give the time” to men she could not use. Each selection was an American “with clout in the war effort.” Randolph was now referred to as “Mr. Pam.” “He threatened to put the entire Anglo-American alliance at risk,” and possibly began to beat Pamela. Averell eventually moved on; Pamela did, as well, to the American intelligence officer Jock Whitney. He also began to provide Pamela with an allowance.

Pamela hosted soirees to pick the brains of guests like Dwight Eisenhower and George Marshall. She embarked on an affair with Journalist Edward R. Murrow; he, Purnell says, smoked during sex, and not in a good, metaphorical way. She also added Bill Paley, Murrow’s boss. Paley, through his media, “became a passionate defender of the British cause.” And Paley paid her, too. Pamela fed Murrow information that would help the British war effort. There were others, as well. Once lovers collided, one offering what he thought was a priceless gift in wartime – Hershey bars. But another lover brought steaks. Pamela occasionally “disappeared.” Purnell surmises for abortions.

The war ended, and her war work ended as well. Pamela wanted to contribute to anti-war efforts. She would not be in a position to realize this vocation till decades later, when she became an ambassador. In the immediate post-war years, Pamela began hopping from one relationship to another. These were not efforts to gain or convey information. Rather she was looking, in Britain the U.S., and France, for love, commitment, and lots of cash. Pam and Randolph finally divorced; he immediately married someone else, whom he did beat. Pamela was involved, again, with Edward R. Murrow, Aly Khan, Elie de Rothschild, and Gianni Agnelli. Aly Khan was a sex machine carrying a hot bag of rosewater-scented and ice-cube chilled bed tricks; that was “fun.” Pamela restored his home. She would become an expert interior designer. Maintaining a lush environment supported her seductions. But Pamela became bored. Aly was all about pleasure; she had once played a key role in fighting fascism. She needed more.

Playboy Gianni Agnelli was heir to the Fiat fortune. He was the richest man in modern Italian history; Fiat controlled 4% of Italy’s GDP. During the war, Agnelli had fought on the side of the Axis powers. Afterward, with Errol Flynn, Aristotle Onassis, and cocaine, Agnelli “partied like crazy people.” “Only servants fall in love,” he said.

Pamela aided Agnelli in overcoming his family’s associations with Mussolini, and in ushering the family and the company into the post-war economic order. She tutored him in being the gentleman. She recruited Greta Garbo to lure her former father-in-law, Winston, to dinner with Agnelli, and she introduced him to future president Jack Kennedy. Pamela was his passe partout. Agnelli became an “uncrowned king” who operated on an “equal footing with world leaders.”

Pamela converted to Catholicism in the hopes that Agnelli would marry her. She aborted Agnelli’s child. No, the conversion to Catholicism followed swiftly by an abortion makes no moral sense to me, either. After lots of affairs on both their parts, scenes, a dramatic car accident, and one murder attempt, Agnelli married a younger princess. He did, though, phone Pamela every morning, and continued to do so for the rest of her life. When Pamela’s son Winston married in 1964, over a decade after the end of their affair, Pamela requested from Agnelli, and received, permission for Winston to use Agnelli’s private island for his honeymoon.

Pamela moved on to Elie de Rothschild, of the centuries-old Jewish banking family. Pamela would later say that Elie’s attentions were “very flattering to me at a time when I needed to be flattered.” Because Elie “could not abide women making any noise during sex, she kept quite as required.”

Elie was married, and did not divorce. Pamela renewed connections with former lovers in America, including Jock Whitney, Bill Paley, and Edward R. Murrow. She was quickly invited to social occasions featuring rich and powerful guests. At one such event Pamela met show business tycoon Leland Hayward. Hayward produced the original Broadway productions of South Pacific and The Sound of Music. In Hollywood he represented big name stars, including Judy Garland, Jimmy Stewart, and Boris Karloff.

Between 1936 and 1947, Hayward had been married to actress Margaret Sullavan. Sullavan committed suicide at age 50. Two of Leland Hayward and Margaret Sullavan’s three children also died by suicide. Their daughter Brooke Hayward would publish a tell-all, Haywire, in 1977, that is brutally critical of Pamela, who, of course, was not responsible for her family’s misery. The genesis of that misery transpired before Pamela ever came on the scene.

“Elie pleaded with her to stay” with him. “Elie later told a friend that Pamela was the only one he had ever loved but his family had closed ranks against her.” Pamela moved in on Hayward. He divorced his wife Slim, who would go on to be better known as Slim Keith, one of Truman Capote’s “swans,” and he married Pamela. Pamela had remained Catholic. To marry a divorced man, she had to have his marriage annulled, and she did so, using her Kennedy contacts to push the annulment.

Pamela insisted that what she did in bed was only a minor percent of her operation. Rather, she knew how to make men feel like kings, and they loved her for it. She turned homes into dream scapes with exquisite and expensive furnishings, art collections, and floral arrangements. During her marriage to Hayward, “She knelt down to remove his shoes the moment he came through the door and brought in a masseuse to relax him. When he made calls, she would listen in on an extension, taking notes to discuss afterward. His bedside table was stacked with books or magazines she thought might interest him, marked up with what she hoped were helpful comments about theater takings, film reviews, or ideas for new plots … She even affected interest in his beloved baseball … Pamela placed Leland and his work at the center of her universe.” Pamela regretted her lack of formal education. Author and publisher Bennett Cerf provided her with a curated library.

Pamela was a rich woman when she married Hayward. He was a spendthrift who, according to Kingmaker, didn’t care about leaving Pamela destitute when he died. When Hayward’s life of heavy smoking and drinking inevitably caught up with him, and he began to have strokes, Pamela sold precious possessions to bankroll his medical care. Hayward was also selling things, albeit secretly. He wanted to live in high style and he admitted to friends that he didn’t care if he left Pamela in the lurch. After he died, friends found Pamela, “her staff mostly gone, the fridge empty and without enough money to by a dress for the funeral … Brooke Astor stepped in to buy her a new one … Leland had left her ‘penniless.'”

Frank Sinatra, as one does, invited Pamela to his Palm Springs home and proposed marriage to her. Pamela applied the brakes. The wife of Averell Harriman – her World War II paramour – had just died. “Pamela was mingling with the guests in [Washington Post publisher] Kay Graham’s Georgetown garden party when Averell walked in.” Band leader Peter Duchin was Leland Hayward’s son-in-law and Averell Harriman’s adopted son. Shortly after Pamela and Averell reunited, Duchin walked into a room and saw “Pamela and Averell entwined on the sofa, her blouse unbuttoned and skirt around her waist.” Averell was 80; Pamela, 51.

After their wedding, when a reporter asked the former British aristocrat if she was in line with Averell’s Democratic politics, she replied, “Whatever he thinks, I’ll go right along with it. ” Pamela “petted and humored and stroked” Averell’s “still robust ego.” In turn, he took up daily exercise to remain attractive to his wife. “She puts my favorite flower by my bed every morning,” Averell told Peter Duchin. Duchin expressed surprise that his adoptive father had a favorite flower. “I don’t know what it is, but she puts it by my bed,” Averell said. A maid ironed the bed sheets every day.

Pamela began tossing around her very wealthy husband’s money. When Averell gave Pamela a television aerial for her birthday, he got the message that that wouldn’t do. Next time it was emeralds. Her son Winston received a lot, and so did others, including servants from her childhood home. She also donated to charities, especially those for victims of domestic violence. “She showed particular care for those who were ill or down on their luck.” Guests might find a Gucci handbag as a gift in their room.

Pamela and Averell became a power couple. There was nobody who wasn’t somebody who didn’t interact with them. Henry Kissinger had a key so he could use their swimming pool whenever he wanted. Jack Nicholson, Warren Beatty, Robert Redford, and Jane Fonda stopped by. They were repeatedly invited to the White House, not just to mingle with domestic movers and shakers, but also to smooth relations with foreign leaders like Yugoslavia’s Josip Tito and Valery Giscard d’Estaing, “whom Pamela knew from her Paris days.” When Averell and Pamela worked on nuclear disarmament, Pamela became the only woman, other than Indira Gandhi, to meet Soviet leader Yuri Andropov in an official meeting. As Kissinger said, “The hand that mixes the Georgetown martini is time and again the hand that guides the destiny of the Western world.”

Pamela formed a political action committee to fund Democratic candidates. She backed Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton, and turned down others, whom she assessed as lacking sufficient electability. Her success at backing the right candidates and contributing to their ultimate victories was “phenomenal.”

Averell developed bone cancer. Journalist John Chancellor said of Pamela’s support for her much older, ailing husband, “I’ve never seen anyone work so hard to keep an ancient oak alive.” After his death, Pamela had a facelift. Pamela wanted no more husbands. She wanted to die as Averell’s widow. But Agnelli continued his daily phone calls. He visited, as well. He possibly stayed the night at least once. And though she was 66 years old, Bill Manchester, a Churchill biographer, called her “One of the sexiest women I’ve ever met.”

President Bill Clinton, grateful for her political mentorship and financial backing, named Pamela U.S. ambassador to France. She served from 1993 till her death in 1997. Paris Match declared that Pamela “turned the scandal of her past into an ornament.” Elie de Rothschild sent a “love and kisses” you’ll-be-a-great-success welcome note. Reagan’s Secretary of State, George Shultz, visited, and found himself “dying to join an animated exchange” in fluent French between Pamela and Valery Giscard d’Estaing. “The talk was substantive,” Shultz would say, with Pamela providing “the spark and the sparkle.” Historian Antony Beevor was “mesmerized” by Pamela. “Her laugh sounded happy … She was satisfied with her life. She was finally in her own place. She was finally in charge,” observed American diplomat Nancy Ely-Raphael. “It’s taken fifty years,” Pamela would say, “to realize I can’t have been all dumb and ugly.”

Pamela’s final years were marred by financial woes. The Harriman fortune had been badly managed. Averell’s relatives wanted an accounting and money from Pamela. In spite of the strain, Pamela played a role, along with Richard Holbrooke, in American intervention in the break-up of Yugoslavia. After swimming twenty lengths at the Paris Ritz pool, she suffered a brain hemorrhage. Agnelli flew to Paris for a final goodbye. President Jacques Chirac posthumously awarded Pamela the Grand Cross of the Legion d’honneur, making her the first female foreign diplomat to receive this honor. A “heartbroken” Bill Clinton posthumously awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Danusha V. Goska is the author of God through Binoculars: A Hitchhiker at a Monastery.