Murder Ballads

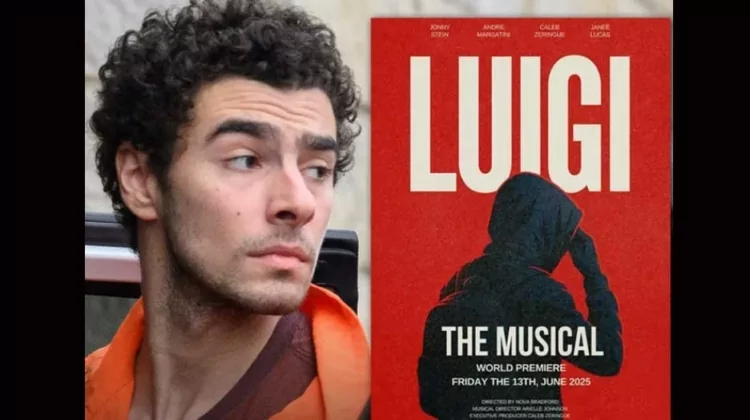

Coming soon: a new musical about Luigi Mangione. (No, I’m not kidding.)

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

It didn’t start with Che Guevara, but Che, surely, is one of the major milestones along the way. By all accounts, he was a psychopath, delighting in the summary executions of purported ideological enemies, including children. But that one famous photograph of him wiped all the blood away. A picture cannot only speak a thousand words; it can erase a million crimes. For young people all over the West in the 1960s and thereafter, Che was a hero, period. In 2008, the top Hollywood director Stephen Soderbergh made a hagiographic movie about Che that ran just under four and a half hours (it was ultimately released in two parts); the title role was played by Benicio Del Toro, whose research for the part included a trip to Cuba, where, he later said, he met “tons of people who loved this man.” To be sure, it’s one thing to encounter Che fans in Castro’s Cuba, where the people have been propagandized to a fare-thee-well and where dissenting views are punished severely; it’s another thing to see free people strolling down the streets of Western cities in Che t-shirts – presumably ignorant of the true heroes who won them their freedom but enthralled by a man who fought to destroy it.

Six years after Che’s death, an infant was born in a manger – no, not really – in Fayetteville, North Carolina. He later lived in Houston, where he served nine jail terms for crimes involving drugs, trespass, theft, and aggravated robbery with a deadly weapon. Still later he moved to Minneapolis, where he was detained for drug possession and suffered a drug overdose. On May 25, 2020, he was stopped by police on suspicion of passing counterfeit money at a grocery store, and died while resisting arrest by a police officer named Derek Chauvin. News of the death of George Floyd spread around the world like wildfire. Mass protests were held everywhere. Countless Floyd murals were created. Riots caused billions of dollars in damage. Leftists used Floyd’s death to spread the lie that hundreds if not thousands of innocent blacks die each year at the hands of white American cops (the real number is in the double digits). As a result of this lie, the movement to defund the police won widespread support, and in many cities the police actually were defunded. The fact that Floyd had died not because of Chauvin’s actions but because of the drugs in his system didn’t matter to Chauvin’s judge, prosecutor, and jury, who knew that if they didn’t throw the book at Chauvin – who ended up being sentenced to twenty-two and a half years in prison – they’d be torn to bits by the mob. By the end of the summer, like Che, his fellow perpetrator of violence, Floyd had been canonized by the left, venerated as a martyr. Last May it was announced that, inevitably, Floyd would be the subject of a movie. Daddy Changed the World was being developed by Radar Pictures, with Floyd’s daughter as executive producer. I can’t wait.

All of which brings us to a new chapter that began early on the morning of December 4, 2024, on a street in midtown Manhattan. Brian Thompson, 50, the CEO of UnitedHealthcare and the father of two sons, stepped out of the Hilton Hotel Midtown and was shot in the back and leg by Luigi Mangione, a computer programming intern and graduate of the University of Pennsylvania who at the time was 25 years old. Thompson died instantly; Mangione fled the city, wearing a medical mask that he lowered briefly at a hostel. Photographs of him with the lowered mask were shown in the media, and many of the people who saw the pictures commented on his attractiveness. Five days after the murder he was arrested while eating hash browns at a McDonald’s in Altoona, Pennsylvania, where a McDonald’s worker had recognized him from the hostel pictures. At the time of his arrest, he was carrying a document explaining his actions; as he put it, “these parasites simply had it coming….the US has the #1 most expensive healthcare system in the world, yet we rank roughly #42 in life expectancy.” He’d killed a man in cold blood, but Che had slaughtered hundreds and become a folk hero; so it happened, as well, to Mangione. Like Floyd, he became the subject of murals. A “Free Luigi” movement gained steam. The Merino crewneck sweater that he wore in the famous photos, an item marketed by Nordstrom, sold out. Fans, mostly giggly young women, showed up for his court dates to show their support. (How curious it is that the same kind of female who finds Donald Trump intolerably vulgar and crude is smitten with this little thug?)

Anyway, the celebration of Mangione is now about to be taken to a new level. On May 1 it was reported that the Taylor Street Theater in San Francisco was rehearsing a new show called Luigi: The Musical that would debut on June 13. Its director, Nova Bradford; its producer, Caleb Zerigue; and its songwriter, Arielle Johnson, share writing credits with Andre Margatini. I’ve never heard of any of them, and can’t find out anything about them online. Are their names real, or pseudonyms? In any event, their opus is set in the Manhattan federal prison where Mangione is now in residence, and its cast of characters includes his real-life fellow prisoners P. Diddy (Janeé Lucas) and Sam Bankman-Fried (André Margatini). The five originally scheduled performances have already sold out, but not to worry – the producers say that they plan to add more dates.

In defense of Bradford and her colleagues, musical comedies have taken on dark subjects before. The ultimate example is perhaps Mel Brooks’s Broadway megahit The Producers (2001), which used music and laughter to mock Nazism – a morally worthy artistic objective. Johnson and Bradford say that they were inspired by another Broadway megahit, Kander and Ebb’s Chicago (1975), which became the Oscar-winning Best Picture of 2002. Like Luigi, Chicago is a jailhouse musical: set in 1928 and based on the real-life stories of two women who committed murders during the 1920s, it’s a truly terrific show about the way in which the modern media transform felons into celebrities. Part of its genius is that none of the characters is sympathetic. The killers, Roxie Hart and Velma Kelly, are both psychopaths, utterly lacking in remorse or empathy. Their lawyer, Billy Flynn, has no regard for truth, justice, or any of the finer feelings (when he sings a tune called “All I Care about Is Love,” it’s dripping with insincerity). And Mama Morton, the prison matron, is as crooked as any of the convicts. The show’s relentlessly dark humor is inextricable from its unvarying cynicism about everything it touches on; its message – which is, ultimately, deeply moral – is that in the world as we really know it, villainy always has a big head start on virtue.

If the creators of Luigi have concocted something along those lines – that is, a show with a healthy moral perspective – well, good for them. But the material that they’ve released about their masterwork suggests otherwise. For example, the show’s adorable tagline is: “A story of love, murder and hash browns.” The official synopsis describes it as “wildly irreverent, razor-sharp,” as “bold, campy, and unafraid,” and as “laugh-out-loud funny and surprisingly thoughtful.” In sum: “If you like your comedy smart and your show tunes with a criminal record, Luigi is your new favorite felony.” This kind of language – about a musical based on a murder that took place less than half a year ago – is too cute and jolly by half. The fact that it’s being staged in San Francisco – Ground Zero for such moral obscenities as Mangioni fandom – leads one to suspect that it doesn’t exactly view its protagonist through a judgmental eye; certainly the Bay Area residents who’ve snapped up all the available tickets are expecting a show that glorifies the glamorous gunman. Then there’s the simple fact that the creators were able to slap this thing together so quickly – which suggests that even if Luigi isn’t a sincere and full-throated billet doux to the killer, it’s something just as morally disturbing: a cynical rush job intended to exploit for profit Mangioni’s disgusting popularity. “We’re not valorizing any of these characters,” insisted Bradford in an interview, “and we’re also not trivializing any of their actions or alleged actions.” Sorry,, but under the circumstances I find that claim mighty hard to buy. I fear, rather, that, like Soderbergh and many others before them, this gang is out to exalt yet another hideous creature who is famous for nothing other than doing cruel and needless violence to his fellowman.